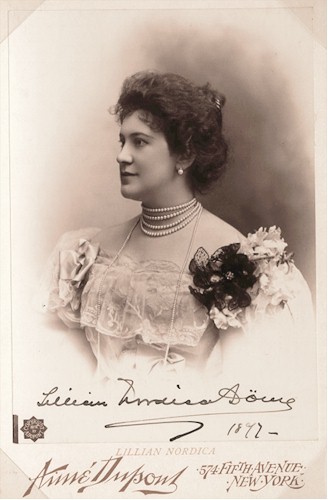

American soprano, 1857 - 1914

(Philip H. Ward Collection of Theatrical Images, 1856 - 1910) Biographical notes:

Lillian Nordica’s story is an operatic fairy tale of sorts, even though the princess did not always live happily ever after. As American as apple pie, this "Yankee Diva" was born in Farmington,

Maine, then went on to become the first American at Bayreuth (as Elsa in 1894) and had her image prominently featured in early Coca-Cola advertising campaigns. She began her vocal

training in Boston at the New England Conservatory, then gave recitals throughout the United States and England (1875 – 78) while barely out of her teens.

Nordica (born with the surname of Norton) studied further in Milan with Sangiovanni, and made her operatic debut there at the Teatro Manzoni in 1879 as Elvira in Don Giovanni. The next year

she was engaged for St. Petersburg, where her varied repertoire included Filina in Mignon (her début role there), Marguerite de Valois in Les Huguenots, Inez in L’Africana, Berta in Le Prophčte

, Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera, The Queen of the Night, Sulamith in Goldmark’s Die Königin von Saba, Cherubino in Le Nozze di Figaro, Simone (a mezzo-soprano role) in Délibes Jean de Neville

, Princess Eudoxie in La Juive and Isabella in Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable.

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

The year 1882 marked Lillian Nordica’s Paris Opera début as Marguerite in Faust, and it was there that she added Ophélie in Thomas’ Hamlet to her already impressive array of coloratura roles. And while she may have trained with that florid art form in mind, Nordica’s voice began to develop a breadth and grandeur which in those early years of her operatic career had already begun to hint of the dramatic (soprano) things to come.

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

In 1883, Nordica made her operatic debut in America as Marguerite in Faust at the New York

Academy of Music, and spent the remainder of the decade touring the United States with "Colonel" Mapleson’s troupe as well as making appearances at Covent Garden (where she debuted as Violetta in La Traviata

), Drury Lane and the Kroll in Berlin. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Valentine in Les Huguenots (one of her most enduring roles) on December 18, 1891, and

remained with the company for eleven seasons, sporadically spaced, through 1910.

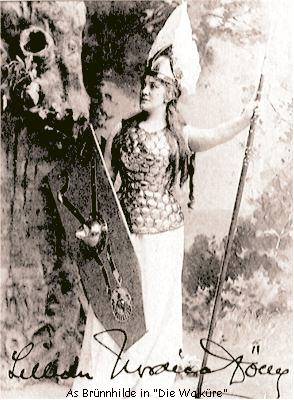

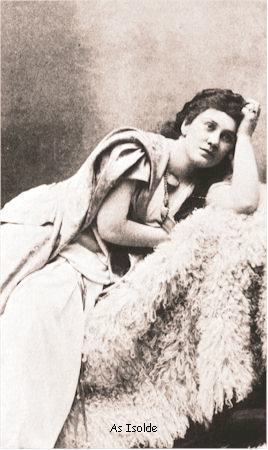

Beginning in the early 1890s, her career as a Wagnerian dramatic soprano gained momentum, and she eventually won acclaim as all three Brünnhildes, Isolde, Elsa, Venus and Kundry, both at the Met and with the Damrosch-Ellis troupe. Frequently, her partner was none other than Jean de Reszke, who was also proving at the same time as Nordica and a couple of others that Wagner’s demanding music dramas could be sung, just as the composer had desired, with flowing legato and a more "Italianate," bel canto style.

Lillian Nordica possessed a kind and loving heart which she lay bare too easily, with frequently unhappy results. None of her three marriages (the middle one being to a tenor named Zoltan Dome) were particularly happy ones. She never had children, which saddened her because she adored them. Late in her career, Lillian Nordica sang with the Manhattan Opera (1907–08) and opened the Boston Opera House in La Gioconda (1909). Her final operatic appearances were to be in that city, as Isolde, in 1913. Late that year she embarked on a recital tour that took her as far as Australia. She nearly missed the ship leaving Sydney on her return, but wired the captain asking him to wait for her, which he unfortunately did. The Tasman wrecked into a coral reef, where it remained for three days, and Nordica suffered from exposure and never recovered. She lingered for months, seeming to improve, only to fail again. She died on May 10, 1914, on the island of Java.

Of Nordica’s voice on records, we are left with few truly satisfying souvenirs. All of her commercial recordings were made for Columbia, and that company’s track record of not being able to cope with operatic voices was not broken in Nordica’s case. She, herself, would have been the first to admit it. "At present I am terribly discouraged about them," she wrote to a friend of her recordings. "... for some reason I do not seem to have any success with them. There is not one which I or my family think fit to put before the public... Ah! Well, I’ll try again; perhaps I’ll be more successful." She wasn’t.

(Philip H. Ward Collection of Theatrical Images, 1856 - 1910)

Columbia’s ledgers show that nearly 40 discs were made by Nordica between 1906 and 1911, but

barely a dozen survived long enough to be published in any form. With few exceptions, the voice on records sounds incredibly small, almost as if she were singing from another room; perhaps

Columbia overestimated the balance between the power of her voice and the fragility of its recording equipment and placed her too far from the horn. It might also be taken into

consideration, however, that even when the earliest of her records were made, Nordica was already nearing 50 and had been singing long and hard for most of those years. Are we possibly listening to all that was left ?

The issue becomes all the more confusing after listening to her excerpts from La Gioconda and Il Trovatore – these are remarkable recordings, if not perfect; they display Nordica’s voice in grand form and compare well with recordings made by her compatriots of the same music. But when one listens for an example of her artistry as a great Wagnerian, her version of "Mild und leise" from Tristan und Isolde, one is confronted with one of the poorest attempts at the piece to be heard on early records. It is, as the record historian J. B. Steane put it, nothing but "a paltry echo of a great assumption."

Jean de Reszke (Tristan) and Lillian Nordica (Isolde)

Too many of Nordica’s surviving records are of insignificant song titles, including "Annie Laurie," which seems to have been a number that no self-respecting soprano of the day could march into the recording studio without. It has been said many times before, because it is true, that her finest moment on record is a strangely haunting excerpt from Erkel’s opera Hunyadi László , sung in Hungarian with a piano accompaniment as opposed to the distracting "orchestra" sound of the day. The climax of the piece, featuring perfect staccato, a sensational shake on the high C-D flat of the cadenza, is positively spine tingling the better part of a century later. We are very fortunate that Nordica was singing at the Met in the early 1900s, when Lionel Mapleson was experimenting with cylinder recordings during live performances. From these we are able to hear her in full flight, away from the confines of Columbia’s studio, and despite the roar of surface noise inherent to Mapleson’s perishable wax cylinders, some truly exciting moments can be enjoyed. Aside from three excerpts from Les Huguenots (sung with Jean de Reszke in 1901!) all of Mapleson’s surviving cylinders are of her Wagnerian repertoire. Nordica rings out rather brilliantly in a number of excerpts from Die Walküre, Siegfried, Götterdammerung and Tristan und Isolde.

My warmest thanks to George Parous and Charles B. Mintzer

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||