Swedish-American soprano (mezzo-soprano), 1871 (1868?) - 1951

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer) Biographical notes:

The New York critic Algernon St. John Brenon once wrote of Olive Fremstad: “She was always an epic sort of creature, moving most comfortably somewhere between heaven and earth... If she

were to come on the scene wearing an old dressing-gown and reading The Ladies Home Journal, you would still rise in your seat and exclaim ‘Ha, now something important is going to happen!”

By most accounts an actress and tragédienne of Shakespearean proportions, Olive Fremstad was also highly skilled in the art of intelligently and carefully using what was basically a

mezzo-soprano voice to become one of the most critically and publicly acclaimed Wagnerian dramatic sopranos of her day. And her day, it must be remembered, included Ternina,

She was born out of wedlock in Stockholm, given the name Anna Olivia Rundquist, and was then adopted by a Scandinavian-American couple named Fremstad. She was raised in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where as a child she studied piano. In 1890 she began her vocal training in New York after singing in church choirs, then studied in Berlin with Lilli Lehmann (this association came to an abrupt end when Lehmann got wind of her husband’s romantic interest in the young American singer) before making her operatic debut as Azucena in Verdi’s Il Trovatore at the Cologne Opera in 1895. During the next three seasons, Fremstad sang in Cologne, Vienna, Antwerp, Amsterdam and Munich, and was engaged for contralto parts in Bayreuth’s 1896 Ring cycles. Fremstad continued her vocal training in Italy, gradually learning and performing roles from the soprano repertoire, but when she was engaged for the Munich Court Opera (1900 – 1903), her most sensational role there was without doubt Bizet’s Carmen.

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

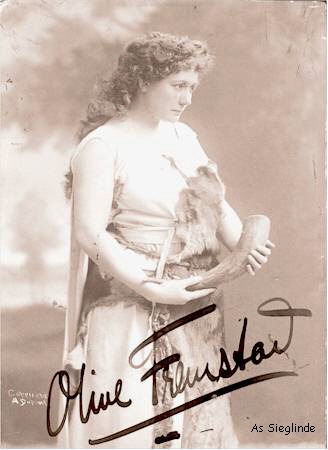

It was in New York, at the Metropolitan, however, that Fremstad joined the ranks of the truly

legendary singers of the so-called "Golden Age." She debuted with the company in November 1903 as Sieglinde in Wagner’s Die Walküre (a performance which included Johanna Gadski’s

first Brünnhilde), and Fremstad was to be a mainstay at the Met for eleven seasons. Her prowess as a singing actress was apparently so awe-inspiring that we may, these many decades later, be

considering an artist on a par with the likes of Maria Callas, based on critical and contemporary accounts of her performances. Fremstad appeared before the public 351 times as a member of

the Met’s stellar roster, most frequently as Venus in Tannhäuser (63 performances), Kundry in Parsifal (50), Sieglinde (47), Isolde (28) and Elsa in Lohengrin (27), but her repertoire there

also included Selika in L’Africaine, Gluck’s Armide, Santuzza (“he little opera positively groaned under the weight of her interpretation,” one critic complained), Giulietta in Les Contes d’Hoffmann

, all three incarnations of Brünnhilde, Tosca, Fricka in Das Rheingold, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Brangäne and a single performance of Salome. American audiences never warmed

much to her Carmen, but she had sung the role opposite Caruso in San Francisco the night before the city was practically leveled by the infamous earthquake and fire of 1906.

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

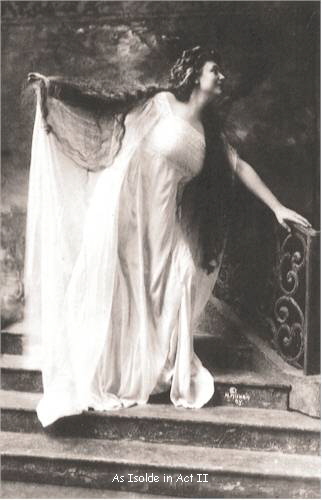

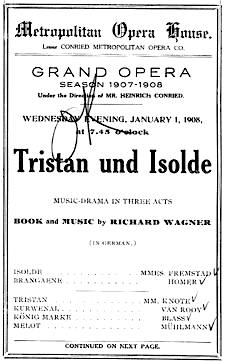

Her interpretation of Isolde seems to have been especially electrifying, and she made her Met

début in the role New Year’s Day 1908 under the baton of Gustav Mahler. Critics frequently remarked, however, that some of the music lay just a bit too high for her comfort, but she

always managed to distract attention from this small matter with extraordinary displays of histrionic skill. Olive Fremstad was truly a prima donna – she lived for her art alone, sulked in a gloomy world

occupied by herself only when not on stage, avoiding her public and compatriots, but rarely the press. “I spring into life when the curtain rises, and when it falls I might well die,” was the

lament she paraphrased for reporters on numerous occasions. “The world I exist in between performances is the strange one, alien, dark, confused!”

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

Unfortunately, with the close of the 1913 – 1914 season at the Met, Olive Fremstad found

herself spending more and more time in her “strange” world, as manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza unwisely allowed her contract to lapse at the height of her popularity. He had tired of her

grandiose manner, frequent cancellations, high salary and, by that time, limited repertoire, and engaged the more versatile and less expensive Melanie Kurt to take Fremstad’s place. She then

toured in recitals for a couple of years, and made appearances occasionally with the Chicago, Boston and Manhattan Opera companies. There was talk of her re-engagement at the Met when

the United States entered World War I, but nothing became of it, and she made her final operatic appearance as Tosca with the Chicago company on tour in Minneapolis in 1918. She gave

what proved to be her final professional appearance, a recital in New York, on January 19, 1920, then asked Gatti-Casazza if he was still interested in her services. She had learned a new role, Leonora in

La Forza del Destino, but that role at the Met now belonged to the youthful Rosa Ponselle. Gatti-Casazza made no response to her inquiry, and Olive Fremstad never sang in public again.

Married to her art, she professed to have no interest in romantic entanglements, although she did foray twice into marital bliss with short-lived results on both counts. Fascinated by men,

Fremstad seemed more at ease moving about in the sapphic circles of her friend Willa Cather, or those of the Misses De Forest and Callendar, for many years New York society’s answer to

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas while the latter couple held court in Paris. Fremstad briefly attempted teaching, but had little patience with anything short of perfection,

and one “lesson” for her unfortunate students required the close examination of a dissected human head preserved in a jar. She was mystified when, now few and far between, her students fled in horror, unwilling to learn

that much about the workings of the human larynx. For Fremstad herself this was but a small matter; when studying the role of Salome she had gone to

the morgue in New York to find out just how much she should stagger under the weight of the head of John the Baptist. On stage, she then staggered a lot.

Recordings: Of Olive Fremstad “on record” we are left with but a handful of souvenirs; the diva herself

would have preferred that we were left with none. “When people play those things in years to come,” she once complained of her recordings, “they will say ‘Oh ho, so that’s the great

Fremstad! Well, I guess she wasn’t so much after all!’” Columbia’s ledgers show that she made approximately 40 records between 1911 and 1915, but only 15 ever saw the light of day. Despite

the fact that Columbia seems to have been especially inept when it came to capturing operatic voices in the acoustical era, most of Fremstad’s records somehow manage to satisfy.

The recorded evidence arguably dispels the controversy as to whether Fremstad’s natural range was that of a soprano or mezzo-soprano. The highest notes, as demonstrated in Brünnhilde’s

“Battle Cry” or Elsa’s “Traum,” are frequently taken with audible effort. Deprived of her histrionic hypnotism, unable to see but only hear, we are today presented with what seems to

have been a very warm, firm mezzo-soprano of uncommon loveliness and a distinctively unique timbre. Listeners even remotely familiar with Fremstad’s voice will most likely be able to identify her singing at once.

(courtesy of Charles B. Mintzer)

She is thrilling in an excerpt from Don Carlo (a mezzo-soprano role) despite the daunting tempo

necessitated by a four-minute 78, and lovely to listen to in Mignon’s "Connais-tu les pays." A pattern develops when one considers that the latter work was also a mezzo-soprano piece, then

compares the purity and security of the voice to a couple of her excerpts from Tosca and Tannhäuser, where occasionally her top sounds somewhat pinched and not always securely

supported. And considering her limited recorded legacy, it is difficult not to resent song titles such as “Annie Laurie” or “Long, Long Ago” for being on the list of her surviving recordings.

Olive Fremstad’s recording of “Mild und leise” from Tristan und Isolde (on Pearl), while one of the better early attempts at the piece, demonstrates no more but no less than any of her

contemporaries’ records that the acoustic recording techniques made it virtually impossible to capture the true magic of Isolde’s transfiguration. The orchestra plays such an integral part of

the drama, and so little of an orchestra sound could be captured; Columbia in particular seems to have employed what sounds like an underwater, one-man band. Add the usual time restrictions,

then be amazed at how Fremstad manages to rise above it all, leaving behind a truly precious souvenir to be cherished.

My warmest thanks to George Parous and Charles B. Mintzer

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||